There were many new developments in ceramics, along with the continuation of established traditions. Three major types of decoration emerged: monochromatic glazes, including celadon, red, green, and yellow; underglaze copper red and cobalt blue; and overglaze, or enamel painting, sometimes combined with underglaze blue. The latter, often called “blue and white,” was imitated in Vietnam, Japan, and, from the 17th century, in Europe. Much of this porcelain was produced in the huge factory at Jingdezhen in present-day Jiangsu province. One of the period’s most-influential wares was the stoneware of Yixing in Jiangsu province, which was exported in the 17th century to the West, where it was known as boccaro ware and imitated by such factories as Meissen.

The Ming regime restored the former literary examinations for public office, which pleased the literary world, dominated by Southerners. In their own writing the Ming sought a return to classical prose and poetry styles and, as a result, produced writings that were imitative and generally of little consequence. Writers of vernacular literature, however, made real contributions, especially in novels and drama. Chinese traditional drama originating in the Song dynasty had been banned by the Mongols but survived underground in the South, and in the Ming era it was restored. This was chuanqi, a form of musical theatre with numerous scenes and contemporary plots. What emerged was kunqu style, less bombastic in song and accompaniment than other popular theatre. Under the Ming it enjoyed great popularity, indeed outlasting the dynasty by a century or more. It was adapted into a full-length opera form, which, although still performed today, was gradually replaced in popularity by jingxi (Peking opera) during the Qing dynasty.

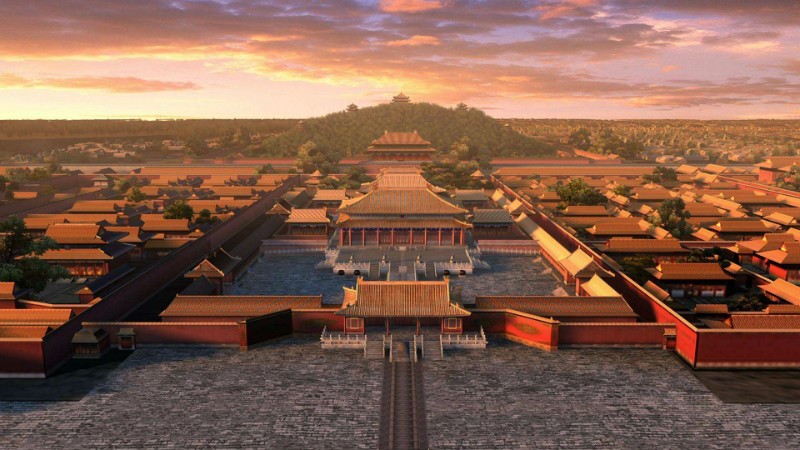

In the end, the greatest achievements accomplished during this time were on architecture. The Forbidden City in Beijing was crafted this time. Porcelain making was also relevant during this time, which contributed to arts of present day.

Books were routinely banned, and theaters shut down.Despite this oppressive atmosphere, some creative work did gather attention, as with the poetry of Yuan Mei and Cao Xueqin’s novel Dream of the Red Chamber.Painting also managed to thrive. Former Ming clan members Zhu Da and Shi Tao became monks to escape governmental roles in Qing rule and became painters. Zhu Da embraced silence as he wandered across China and his depictions of nature and landscapes are imbued with manic energy. Shi Tao is considered an artistic rule-breaker, with Impressionist-style brush strokes and presentations that predated Surrealism.

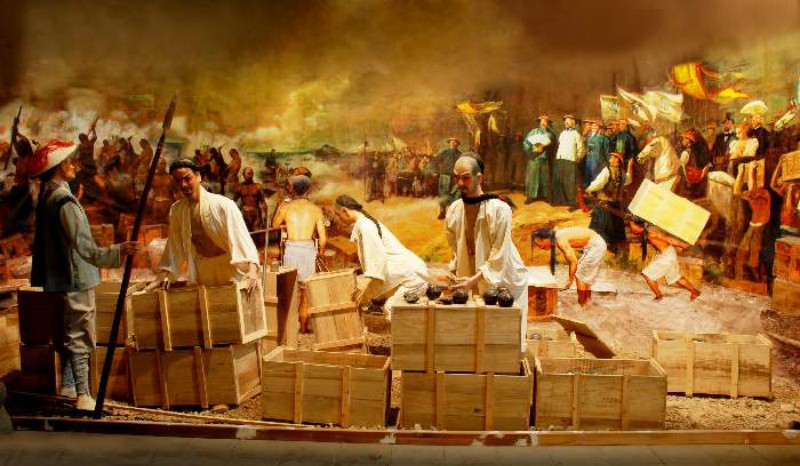

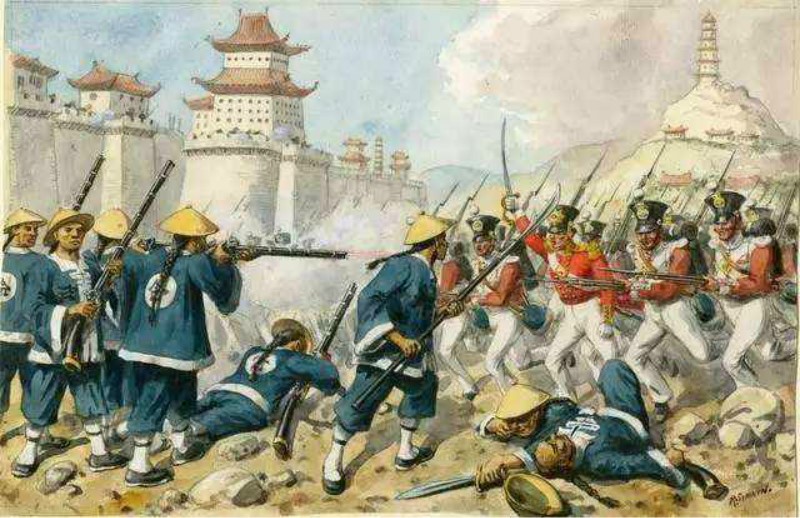

Opium was used medicinally in China for centuries, but by the 18th century it was popular recreationally. Following its conquest of India, Britain cultivated and exported opium to China, flooding the country with the drug. An addiction crisis followed. A ban was attempted, and smoking opium outlawed, but British traders worked with black marketers to bypass laws. Military confrontation became likely, and soon British forces shut down Chinese ports. Among many concessions during negotiations, China was forced to give up Hong Kong to the British.

A second Opium War was waged from 1856 to 1860 against the British and the French, bringing more unequal agreements.Christian missionaries were allowed to flood the country, and western businessmen were free to open factories there. Ports were leased to foreign powers, allowing them to operate within China according to their own laws, and opium addiction rose.