Guihai Stele Forest Museum

Located in the southwestern corner of the renowned Seven Star Park, the Guihai Stele Forest Museum stands proudly at No. 1 Longyin Road, Qixing District, Guilin City. Covering a total area of 40,795 square meters, with a building area of 1,463.5 square meters and exhibition space spanning 7,382 square meters, this museum is a specialized treasure trove showcasing the stone inscription culture of Guilin.

While the breathtaking landscapes of Guilin are celebrated far and wide, few are aware that Guilin's stone inscriptions are equally deserving of acclaim. Since the Eastern Jin Dynasty, countless scholars, poets, and literati have been drawn to Guilin, scaling its mountains and strolling by its rivers, immortalizing fleeting moments of inspiration by engraving them into the rocks. With over 2,500 cliffside inscriptions, sculptures, and scattered steles adorning more than 30 famous mountains and grottoes in and around central Guilin—such as Duxiu Peak, Diecai Hill, and Fubo Hill—Guilin has earned the distinction of being home to the largest number of stone inscriptions and carvings in China. This has led to the saying among experts: "For Tang steles, look to Xi'an; for Song inscriptions, look to Guilin." The claim that "no mountain in Guilin is without a cliffside inscription" is no exaggeration.

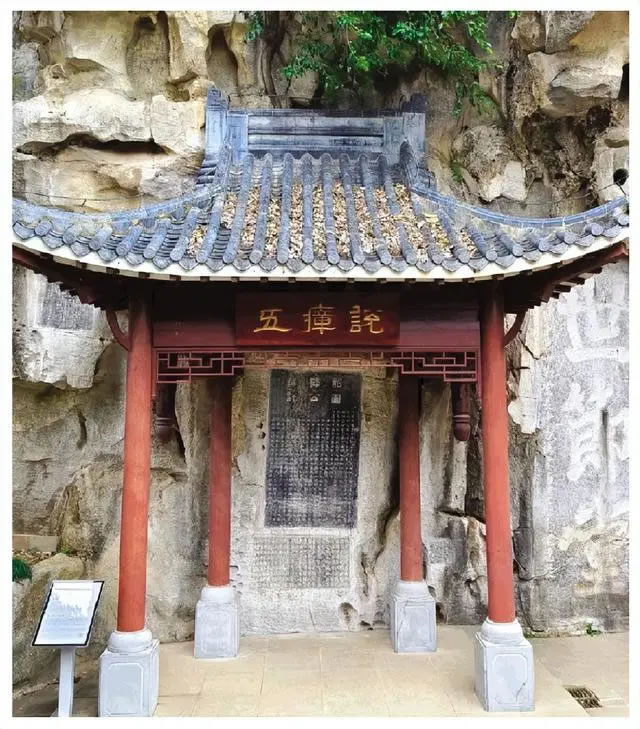

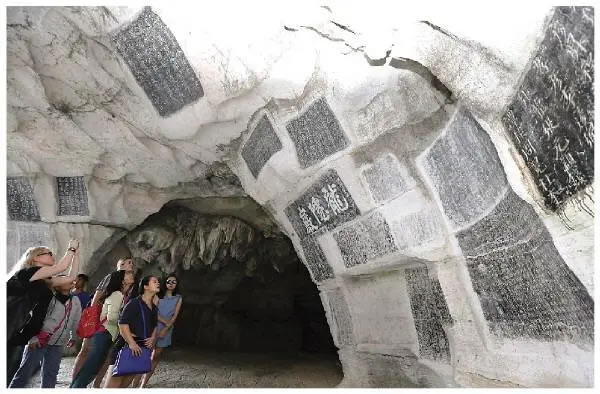

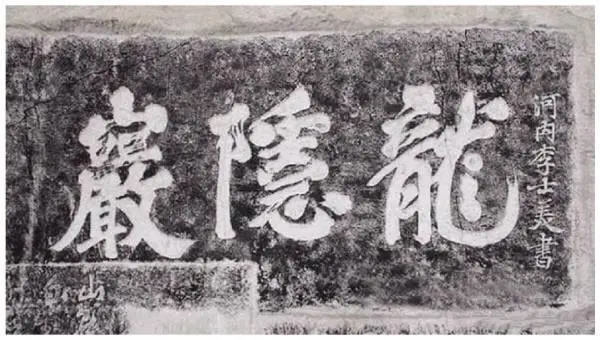

Among these inscriptions, the most renowned and representative is the Guihai Stele Forest, composed of the stone inscriptions found in Longyin Cave and Longyin Grotto. The cliffs are nearly covered with inscriptions, and the walls, filled with steles, seem like a forest of stone. The Guihai Stele Forest is like a small window through which one can glimpse the splendid 1,700-year history of stone inscriptions in Guilin.

"Among all landscapes, Guilin's are supreme. During the Tang and Song dynasties, scholars crossed into Lingnan area, leaving their names and poems inscribed on the cliffs, nearly covering all over them. Guilin's stone inscriptions from these eras are unmatched," wrote Ye Changchi, a renowned epigrapher of the Qing Dynasty, over a hundred years ago, expressing his admiration for Guilin's stone inscriptions.

The Guihai Stele Forest stands as a quintessential representation of Guilin's stone inscription culture. On the southern slopes of Yaoguang Peak in Crescent Hill, within Seven Star Park, at the banks of the Xiaodong River, Longyin Cave and Longyin Grotto, ancient inscriptions whisper from the weathered limestone cliffs, as if a white-bearded storyteller were gently recounting the tales of Guilin's millennia-old past.

Zhu Xiyan, a former Transport Commissioner of Guangxi, once remarked, “Among the caves of Guilin, Longyin reigns supreme.” With its jade-like cliffs, meandering clear waters, and a legendary connection to dragons, Longyin Cave and Longyin Grotto have long been a sanctuary for poets and scholars seeking solace and inspiration.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, the Xiaodong River flowed abundantly, providing an idyllic passage for literati who would often drift downstream in boats, entering Longyin Cave from its southern mouth. After disembarking, they would climb the steps to Longyin Grotto, all the while marveling at the majestic peaks and serene waters on either side. It was common for these scholars to pause by the river, sharing a cup of freshly brewed tea, playing melodious tunes on string and wind instruments, and savoring the harmonious blend of nature’s sounds. These experiences are forever immortalized in stone inscriptions. These stone inscriptions are like ancient versions of social media posts, left behind by our predecessors to transcend time and space.

On a midwinter day in 1064, the first year of the Zhiping Era, Yu Zao, the Judicial Commissioner of Guangxi, along with Transport Commissioner Kong Yanzhi, former appeasement officer Yao Yuandao, and the new prefect of Gongzhou, Ding Chun, enthusiastically explored Longyin Grotto. Their journey, recorded on the rock itself, began at Shouning Temple and continued to Qinglin Temple, with a brief rest at Fengdong Cave (Wind Cave). After ascending to Qixia Cave, they returned to their boat, docking at Longyin Grotto, where they indulged in food, wine, and poetry as the sun dipped below the horizon.

Another stone inscription on Longyin Grotto, the Song Jiongtong and Huang Jidao Inscription of Seven Friends, tells of a reluctant farewell. On the 16th day of the 9th lunar month, 1150, seven friends, including Huang Jidao, gathered at Xiaoran Pavilion to bid each other goodbye. After their meal, they visited Longyin Grotto, passed through Qixia Cave, climbed mountains, and gazed at the water, all while feeling the heavy weight of impending separation. As night fell, they returned to Xiangnan Tower for a final, small gathering.

By 1210, during the 3rd year of the Jiading Era of the Song Dynasty, a pavilion called Pingting was erected to the south of Longyin Grotto (though it no longer exists today), and nearby, Shijia Temple, Canluan Pavilion, and Huancui Pavilion were built. During the Ming Dynasty, Yiyun Pavilion was added, enriching the cultural and scenic offerings of the Longyin area and attracting even more scholars who left their mark on the stone. Among these inscriptions are masterpieces of poetry by Li Bo and Fan Chengda, calligraphy by Yan Zhenqing and Huang Tingjian, essays by Yuan Hui and Zhu Xi, and paintings by Wu Daozi, all forming a brilliant constellation of art and literature in stone.

In the Longyin Cave and Longyin Grotto area, beyond the inscriptions left by famous scholars and literati who visited to immerse themselves in nature's beauty, there exist works that were not originally created here but were later engraved upon these stones, allowing future generations to admire and reflect upon them. Among these, a prominent example is Shi Manqing's Farewell to Ye Daoqing from the early Song Dynasty. This piece is located in Longyin Grotto and was written in 1033 during the Mingdao Era and engraved in 1195 during the Qingyuan Era. The work commemorates a gathering of sixteen individuals, including Shi Yannian (better known as Shi Manqing) and Fan Zhongyan (Fan Xiwen), who assembled in Bianliang (modern-day Kaifeng) to bid farewell to Ye Qingchen as he departed to assume his post in Jiaxing, Zhejiang. The entire piece is composed of 66 grand characters written in regular script, exuding the robust strength of Yan Zhenqing's style and the grace of Liu Gongquan’s brushwork. The strokes are natural and majestic, displaying a calm and dignified demeanor with an extraordinary presence. It is revered as a divine treasure, a rare masterpiece of calligraphy. Shi Yannian, a renowned poet and calligrapher of the Song Dynasty, was a leading figure in the bold and heroic poetic style of early Song. His surviving works are exceedingly rare, making this farewell inscription a highly cherished gem by scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Data reveals that Longyin Grotto and Longyin Cave house 213 stone inscriptions dating from the Tang Dynasty to the period of the Republic of China. Among these, one is from the Tang Dynasty, 111 from the Song Dynasty, one from the Yuan Dynasty, 42 from the Ming Dynasty, 26 from the Qing Dynasty, and 32 of unknown age. These densely packed inscriptions vividly bring historical cross-sections to life before our very eyes.

Beyond poetic inscriptions and commemorative gatherings, Longyin Cave and Longyin Grotto have witnessed significant historical moments. Through them, we can touch the veins of China’s millennia-old history.

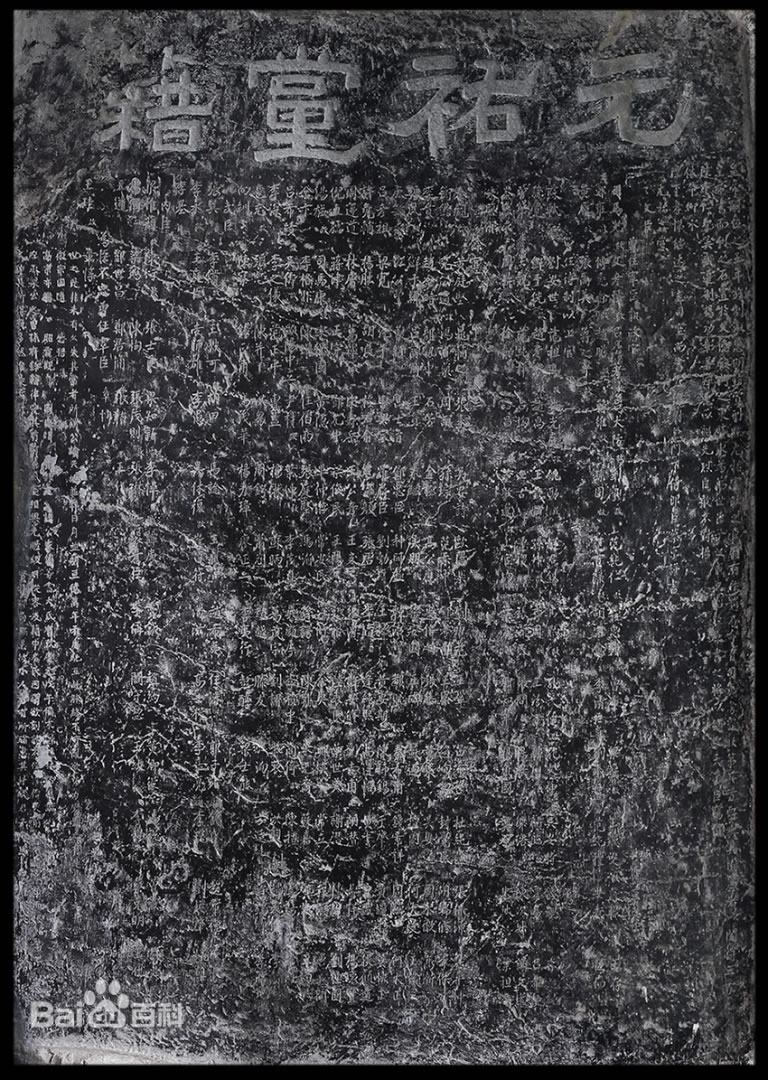

One of the most notable inscriptions within Longyin Grotto is the Yuanyou Party Membership Stele, which records a fierce political struggle during the reform period of Wang Anshi in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127, AD). In 1105, during the fourth year of the Chongning Era, Chancellor Cai Jing, wielding considerable power, used opposition to the old party as a pretext to fabricate charges and suppress his rivals. Many renowned literary figures, such as Sima Guang, Wen Yanbo, Su Shi, Qin Guan, and Huang Tingjian, were among the 309 individuals he branded as “traitors.” Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty, Zhao Ji, personally wrote the texts and had them inscribed on the stele, placing it on the eastern wall of the Wende Hall gate, and ordered Cai Jing to have similar steles erected across the country, proclaiming the decree to all. However, the very next year, the emperor, “moved by reflection,” ordered the destruction of these steles, leaving none in existence. Ninety-three years later, in 1198, during the fourth year of the Qingyuan Era, Liang Lü, the great-grandson of Liang Tao, who had been labeled a Yuanyou Party member, came to serve in Guilin and re-engraved the Yuanyou Party Membership Stele within Longyin Grotto. This stele holds immense historical significance and value, serving as a crucial entry point for studying Song Dynasty history. After reading the stele, Ming scholar Luo Zuo was moved to compose a poem: “Five hundred years have passed since Yuanyou Era, yet the names of the party members remain here. The declining Song court’s efforts to restore order were unceasingly hindered by slanderous words. The rock is more resilient than bamboo slips, covered by vines like a golden vessel. Virtuous men’s fame lasts forever, while slanderous plots by treacherous officials are but vain efforts.” From condemnation to praise, the silent rock speaks across the ages. Time has tested loyalty and treachery, making the virtue of integrity even more precious.

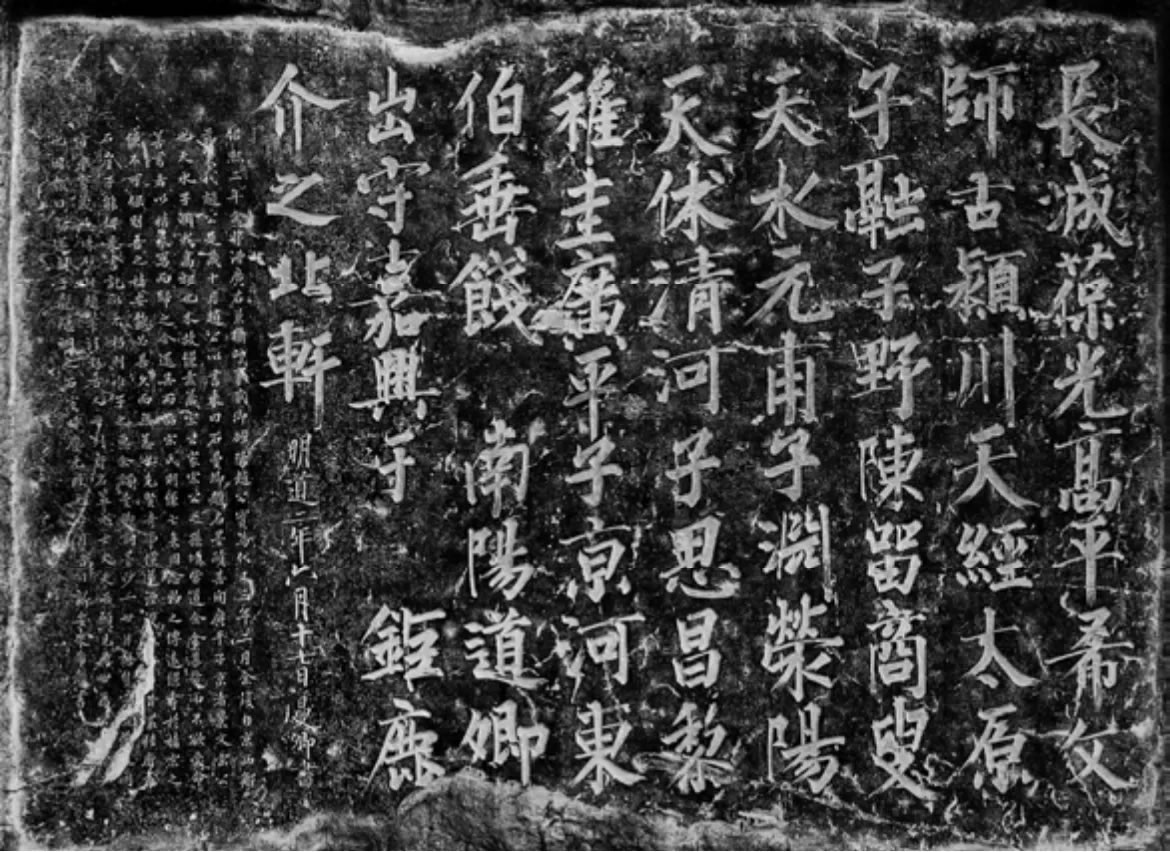

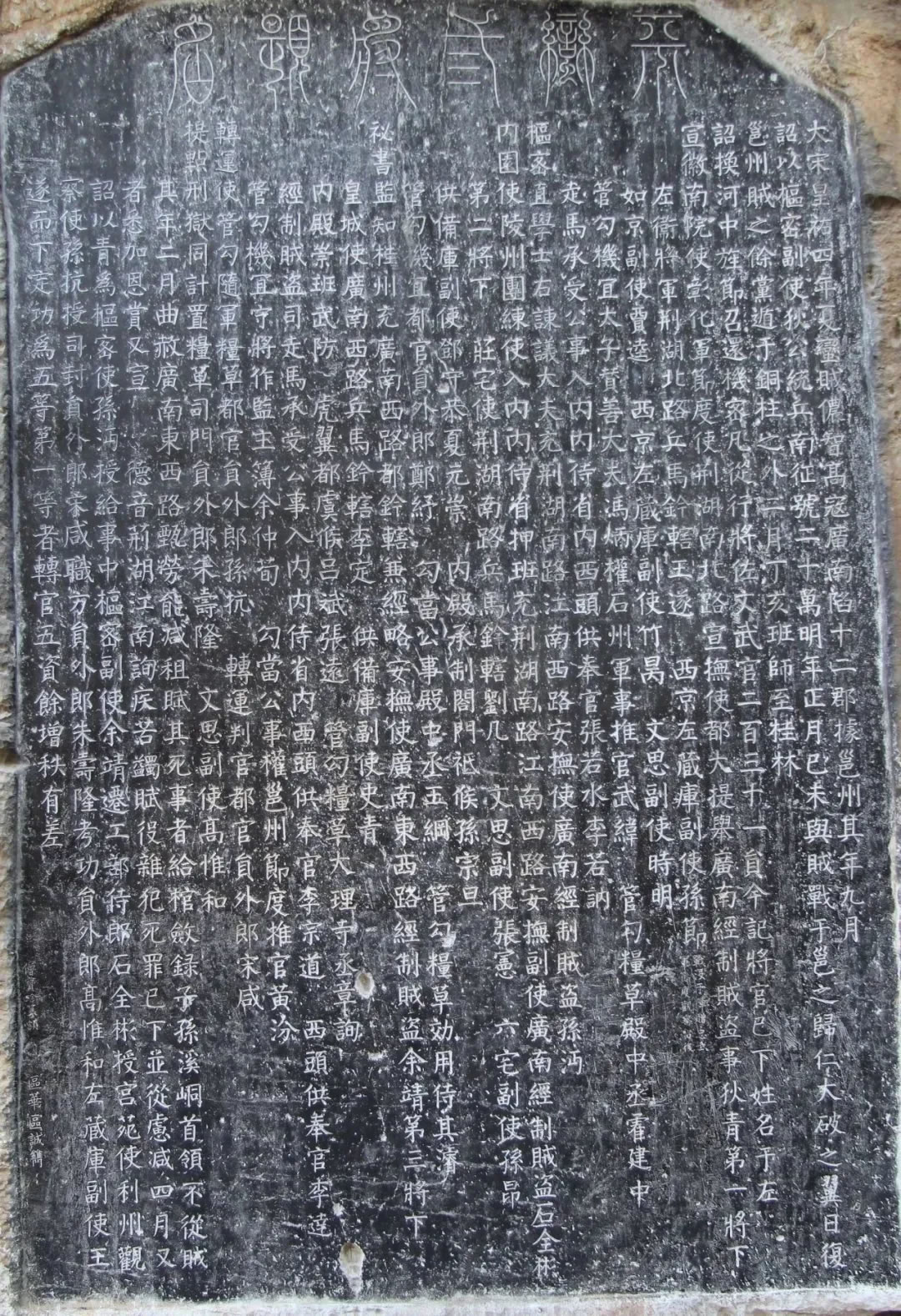

In Guilin, two stone steles represent the relationship between the central government of the Song Dynasty and the local ethnic minorities of Guangxi. One is the Great Song Pacifying the Barbarians Stele, carved on the western face of Tiefeng Mountain; the other is the Stele of Three Generals Who Pacified the Barbarians, located right here within the Longyin Grotto. The Stele of Three Generals was carved in the fifth year of the Northern Song’s Huangyou Era (1053). Standing 3.79 meters tall and 2.40 meters wide, it is inscribed in regular script, using just over 740 characters to recount the exploits of Generals Di Qing, Sun Mian, and Yu Jing, who led troops southward to quell Nong Zhigao’s rebellion against the Song Dynasty. In 2023, this stele, along with three other Song Dynasty cliff inscriptions from the Guihai Stele Forest—Mei Gong’s Discourse on Miasmas, Farewell to Ye Daoqing, and Yuanyou Party Membership Stele—was selected by the National Cultural Heritage Administration as part of the first batch of ancient famous stele inscriptions.

The stone inscription Mei Gong’s Discourse on Miasmas is a work that sharply criticizes the ills of the time. The author of the inscription, Mei Zhi, was a scholar of the Longtu Pavilion in the Northern Song Dynasty and served as the prefect of Zhaozhou (nowaday Pingle, Guangxi) during the early years of the Jingyou Era. Guangxi had long been plagued by miasmas, earning it the nickname “the land of pestilence,” with Zhaozhou being the worst affected. After being exiled to Zhaozhou, the already frail Mei Zhi surprisingly did not fall victim to miasma. This led him to realize that the natural miasma was not as terrifying as the “miasma” of government oppression—harsh taxes, unjust punishments, excessive banquets, exploitation of the people, and the chaos of concubine selection—which he saw as the true destroyers of people. Thus, he penned the Discourse on Five Miasmas, condemning the “miasmas” of extortionate taxation, judicial corruption, excessive feasting, avarice, and the indulgence in women.

Next to Mei Gong’s Discourse on Miasmas is another Song Dynasty inscription, The Hall of Generations, inscribed by Fang Xinru, an official who was thrice sent on diplomatic missions to the Jin Kingdom. In the sixth year of the Jiading Era, Fang Xinru was reassigned from Guangxi’s Judicial Commissioner to the Transport Commissioner. His father, Fang Songqing, had also served as an official in Guilin and was well-loved by the people for his many good deeds. In the eighth year of Jiading, to remind himself to always keep the welfare of the people at heart, Fang Xinru had the three characters “世节堂The Hall of Generations” inscribed as a tribute to his father’s legacy.

The saying “For Tang steles, look to Xi'an; for Song inscriptions, look to Guilin” is a testament to the historical and cultural significance of the Guihai Stele Forest and its Museum. This heritage not only underscores Guilin’s status as the “most beautiful landscape under heaven” but also as a national historic and cultural city. On June 25, 2001, the Guilin Stone Inscriptions, including those in the Guihai Stele Forest, were listed by the State Council of China as part of the fifth batch of National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units.